This feature first appeared in the July 2015 issue of Rugby World magazine.

SOMETHING SHOULD have been jarred loose as New Zealand met France in the 2011 Rugby World Cup final, 24 years after the pair had last faced off at Eden Park to battle for the Webb Ellis trophy. The Kiwis should have bossed the showcase against a French side caught in a bipolar pull between their heroic players and comedy villain head coach Marc Lièvremont. But benumbed by the occasion, the All Blacks stuttered to the 8-7 win the country desperately needed.

On that day New Zealand had to dig down to their boot-tongues for the required effort. They shed their chokers tag. They won every game on their way to the big one. It impressed in terms of outcome, if not performance.

That outcome: there is so much that goes into snatching a World Cup. When you look at the score from the last final and see a one-point difference, you can imagine the plans and sessions and speeches and images that helped make the tiny difference. It was special for the All Blacks of 2011 because of their years of hurt, but in every final to date there have been little moments and messages in the build-up that have helped the team to victory.

So the question is: can a team win the Rugby World Cup because of their off-field work? To answer this we ignore the games themselves and look at the overall campaigns, at the role of squad harmony, training and marketing.

PULLING TOGETHER

In 2012, the NZ Herald spoke to Sir Brian Lochore, asking him to compare the All Blacks of that year with a side he played in during the 1960s, a side that racked up 17 Test wins in a row. He said: “Moulding teams is about having trust in each situation and knowing what your team-mate is going to do.”

It is worth throwing a refresher into the mix here: this is the same Sir Brian Lochore who coached the 1987 All Blacks at the first-ever World Cup.

However, while many insist that New Zealand were preordained to win the inaugural World Cup, such was their superiority over the rest of the field in terms of style, guts and ability, Lochore had his work cut out to get his team in the right frame of mind. New Zealand had lost Tests in the build-up to the World Cup, having been forced to field a ‘Baby Blacks’ team in the wake of bans being handed to the renegade men who toured South Africa – then a disgraced outpost because of apartheid – as the Cavaliers the year before.

The 1987 team had to believe they could do it and reintegrate the players who had been pushed out of the loop. They took time off in the knockout stages to get away from the pressures of a World Cup, escaping into Wellington farmland. They tried to stay grounded. And they won the final at a canter, 29-9 against the French.

The best team tends to win, sure, but the best teams always have their ducks in a row and a harmonious squad too. Look at the Springboks of 1995. They felt the need for unity both on the field and off it. We often talk about the power winning that World Cup wielded, as South Africa sought to come together as one vibrant country post-apartheid under Nelson Mandela. What we often forget is that it must have been bloody hard for the team to do. This was the legacy of their late coach, Kitch Christie.

MIND GAMES

But how did the 2011 crop do it? Firstly, the group identified that the boring old adage of ‘we’ll take it one game at a time’ wasn’t going to cut it. In 2007 they’d tried that and blown up. Before 2011, the team’s Mental Analysis and Development (MAD) group, headed in part by psychiatrist Dr Ceri Evans, deduced that the best results actually came from preparing to win every single game and ignoring form before the tournament.

Perhaps more importantly, the team were prepared for disaster. In 2007 they could not comprehend France smashing them apart. Injuries distressed them. But in 2011 New Zealand knew they could lose stars, catch a referee who was card-happy or have to play in repulsive conditions. In short, they embraced the pressure.

BUYING INTO ENDEAVOUR

When everyone is convinced by the team ethos, though, where does the advantage come from?

Upon being asked about this very subject, 2003 World Cup winner Phil Vickery begins to talk about sacrifice. Not that general stuff all elite athletes do, like giving up booze or waking up early. Vickery is talking about stuff that drives you to extremes every single day.

“This sounds a bit psycho and it’s maybe where the whole Raging Bull thing comes from,” the former tighthead says with a laugh, “but I can remember coming back from injury and going for long walks up the steepest hill I could find past the forest near where I live. I couldn’t run at the time – I could barely stand up – but I’d walk up and down it and picture the faces of every single person I hated as I stamped down. I’d do that over and over again.”

He uses this as an example of the mindset of a winner. He was no saint, he insists, but he was driven to achieve and would find any edge he could. He had to, even if that meant that he was pushed through training that made him miserable, time after time.

“In 2003 I used to get sent home from training with extras to do. I was never a great trainer but you’ve got to do them because it was so competitive. Whenever I got told to do fitness extras I would do them, because I knew Back would be doing them, I knew Hill would be doing them, I knew Dallaglio would be doing them, I knew Johnson and Wilkinson and Greenwood would be doing them…” Here he rattles off the name of almost every single England squad member from 2003. “I knew those f***ers would be doing the extras and more!”

MARGINAL GAINS

We now live in the age of ‘marginal gains’, that principle so adored in professional cycling where an athlete will shave off anything or eat any vile supplement because it makes the competitor or team all the more efficient. In 2003, this was going on without a name being given to the movement. England had more staff than anyone else, tighter kit than the competition and tailored training plans and diets. They also had Dr Sherylle Calder.

If you don’t know of Dr Calder, you should. She is the only person to have won back-to-back World Cups, first with England in 2003 and then with South Africa in 2007. She is a specialist in ‘visualisation’ training. That means training the eyes and mind to scan and anticipate.

“You absolutely have to do what other teams aren’t doing, because it could be one decision in one game that wins the World Cup,” Calder informs Rugby World. In 2003, England had it all. In 2007, South Africa didn’t even have a nutritionist. But Calder insists they had the edge where it mattered; they had the edge with their skill-set.

“All teams work on physicality, nutrition, set plays… but so many neglect skills. I watch the Aviva Premiership and Super Rugby and there are so many basic errors.

“Not enough time is dedicated to skills and decision-making. You’ve got to train your eyes and brain. We found, using a ten to 15-minute training session, that we could make 800 to 1,000 decisions in a session, with some things the player had not seen before. You’ve got to play what you see. Even with South Africa we had some guys who were really bad under the high ball, dropping six out of ten. We trained around those skills in practice and gave the players the confidence to know they could catch it.”

Training evolves and you have to be prepared for that. For example, Rod Macqueen was something of a visionary in 1999 when he coached Australia to the title because he embraced statistics. The team trained themselves to kick out of their own half after three phases because the stats showed referees were penalising those with the ball in their own territory for several carries.

Of course no team is totally robotic. Vickery baulks at the notion. “We weren’t like clones,” he insists. There were too many big characters for that to be the case.

It appears that having big characters in your group is vital to success. Especially if you want to control how the rest of the world views your team.

INFORMING THE PUBLIC

Alastair Campbell has recently written his book Winners, a look at those who have achieved success in sport, business or politics. The ‘spin doctor’ helped Labour to political triumph and was part of Sir Clive Woodward’s back-room team on the disastrous 2005 Lions tour. Does he think teams can win it all off the park?

“The obvious answer is no,” he says. “But whether a team does well is about preparation and motivation.”

Campbell agrees that to win you have to innovate faster than your competitors, citing skintight kit, shirt changes at half-time, even Holland substituting their goalkeeper just before a penalty shoot-out in the last football World Cup. But in a World Cup, where every team has media obligations and the public are baying for their favourite personality’s input (especially if you ban players’ newspaper columns, as England are doing at RWC 2015), press officers face a juggling act to give access whilst also protecting their sheepish superstars.

“When I was with the Lions I never bought the idea that everyone had to do their share of media work,” he insists. “You want to engender confidence and teamship, but the head coaches and star players do the most. I remember flying out on the day Liverpool FC won the Champions League and Jonny (Wilkinson) said to me that he knew there would be a lot of media interest in him but he didn’t want to be treated any differently.”

For the political adviser, games cannot be won or lost in an interview, but if you shield people at the right time you can get the most out of them.

Campbell continues: “I spoke with Andy McCann, the Wales psychologist (for his book). He said a lot of players, a lot of the time, are sitting around bored, looking at social media. And some of them were packing it in because of abuse. I’d tell them, ‘Do it, but don’t take it seriously!’ Sometimes we get stuff out of perspective. But a siege mentality can be helpful. Fergie (Sir Alex Ferguson), Clive (Woodward) and Dave Brailsford (head of Team Sky cycling) all felt the siege mentality was useful. It makes a difference – it is not massive, but if you can do even 5% better…”

Perhaps looking after the athletes’ minds isn’t just about preparing them for the worst on the paddock, but walking on the eggshells between pushing them to be seen and heard publicly, and keeping them quiet and invisible. They are not children, but the smallest insult to their mental rest could damage the less confident player.

GET THE MARKETING RIGHT

Anyway, you can promote an image without the active participation of the personalities, and that in turn could help engender confidence. At least that’s according to Mike Leeson, the managing director at advertising and marketing group Golley Slater. Leeson believes that because a certain type of athlete thrives in the spotlight, good publicity can help provide 1% extra here or there.

“Advertising them well can give them a boost, depending on what you are saying about them,” he says. “Ultimately rugby is about 15 big guys on the field, but it is also about the emotion that you can overtly associate with them and how that is captured.

“In the upcoming World Cup we are going to see more teams claiming to be something. So, for example, if a team is saying they are the fittest sports team of all time, it’s not just what they are saying about themselves, but that, de facto, all the other teams aren’t the fittest.”

According to Leeson, this is how he would approach the pre-World Cup time as a Test team, marketing themselves to create a certain image of them and their stars and then getting those players to send out ‘spin-off’ sentiments through social media, to hammer home the core message. If everyone is saying you are the fittest and then a star player uploads a video of himself working hard in the gym, you further highlight the point.

Leeson believes that sponsors can help too.

“There is such a thing as momentum,” claims Lance Bradley, the managing director of Mitsubishi UK, who will be the official shirt sponsor of Gloucester next season. His company have come through the economic lull of the 2000s and are growing, even innovating. But while it makes sense to support the company’s local pro side and advertise on a team’s shirt and stands, he genuinely believes sponsors can help a sports team – even if, as with the World Cup, sides are not allowed visible kit sponsors.

It will be a tiny push, sure, but it’s a push none the less as a sponsor can make it feel like you are part of something big; like you are on the ground floor of a major project. Knowing a big company is behind you may only really make up a difference of half a percent, Bradley suggests, but all the little bits do add up.

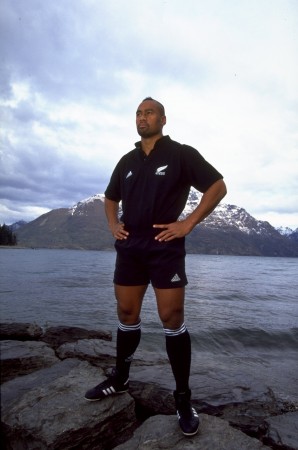

This is anecdotal stuff, but it must be better to have a major sponsor than not. Remember when Adidas were fresh on the scene in New Zealand? Sean Fitzpatrick does, and he said as much in his book Winning Matters.

In it, he relays the tale of how Adidas changed the All Blacks’ famous socks to incorporate three stripes rather than the traditional two. It was a minor style tweak but one which enraged a number of Kiwis. So Adidas made an advert capitalising on emotion, history and the need to keep progressing. It was schmaltzy stuff but it won over the masses. Fitzpatrick explains: “I mention this advert because it highlights that you can sell even difficult changes if you engage with people, talk to them and recognise their map of the world and how they see things. If you are straightforward enough, or perhaps brave enough to tackle the issues that arise out of change with honesty and directness, you can make things happen.”

CONCLUSION

Do not discount the extras. Every little helps, as they say, and you stand more of a chance of success if you are a good side with a strong team ethic, training that everyone buys into, a controlled media image, big characters, protected stars and good sponsors. If you are just another good team that ends up failing, you could forever wonder, ‘What if we’d only done that tiny bit more?’