Examining the data behind the tries England racked up this year can tell us a great deal about the identity of Eddie Jones’ team

Self-awareness spurs ambition like nothing else. Despite a perfect year in terms of results, Eddie Jones’ England need no reminding of their standing in the global order. With New Zealand occupying the coveted top spot, they are acutely conscious of their position behind them – very much in pursuit.

Every training session exudes a restless desire for improvement. In matches, England have developed an intelligent, adaptable autonomy. Starting his tenure with 13 consecutive wins, Jones has imparted tactical clarity. And England’s 46 tries underline this identity.

A time and a place

Recruiting forwards coach Steve Borthwick, his lieutenant with Japan during a remarkable 2015 World Cup campaign, Eddie Jones sought to mend England’s set-piece. He wanted England’s scrum to be versatile – a platform for strike moves as well as a penalty factory.

Prolific lineout possession, providing either muscular driving mauls or fast, off-the-top ball, was another target. Besides his leadership, the throwing of new captain Dylan Hartley proved a vital attribute to the team. Though he only turned 26 last February, lineout guru George Kruis was another pivotal figure.

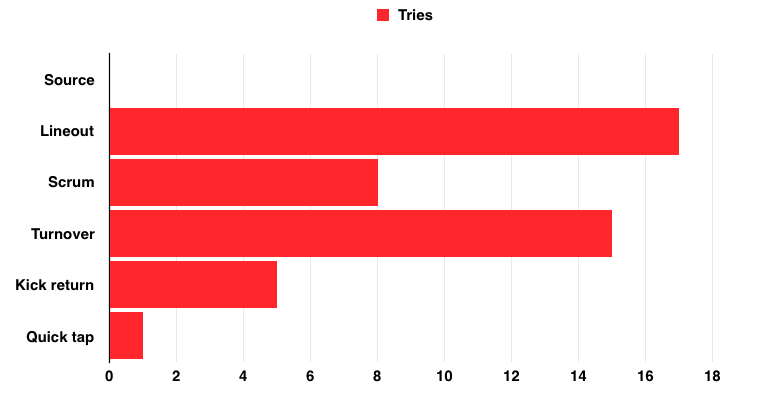

Jones also aimed to reassert an aggressive, proactive England defence, entrusting this task to Paul Gustard. An examination of England’s tries by source demonstrates how these priorities paid off:

Of 46 scores, 25 began at either scrum or lineout. A further 15 arrived after a turnover – forced in the tackle area, at the breakdown or by way of an interception.

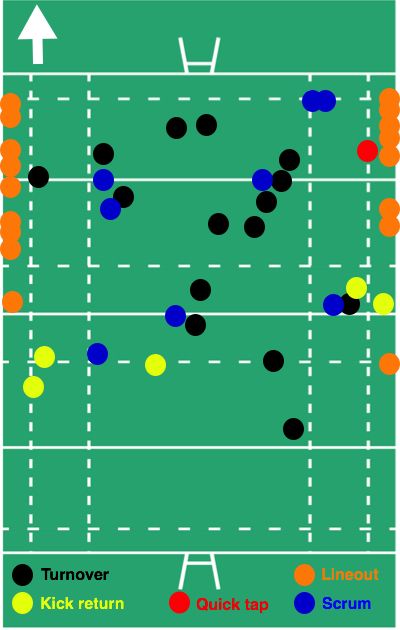

The map below plots the location at which each try was initiated:

Close-range set-pieces speak for themselves here. As we will explore later, the power and cohesion of England’s pack is impressive. But try-scoring scrums from the opposition 22 and further back – three of them on and around the halfway line – indicate a willingness to use the set-piece as a launchpad.

Billy Vunipola burst from the base of scrum on the France 10-metre line in Paris, foreshadowing a cute Ben Youngs grubber into the path of Anthony Watson. The five-pointer helped seal the Grand Slam.

Of the 15 try-scoring turnovers mentioned earlier, two thirds occurred beyond the 10 metre-line of England’s opponents. This hints at an ability to control territory with canny game management and an effective kicking game, led by Youngs and the midfield axis of George Ford and Owen Farrell. Evidently, attacking from deep against England’s claustrophobia-inducing line-speed comes with huge risk.

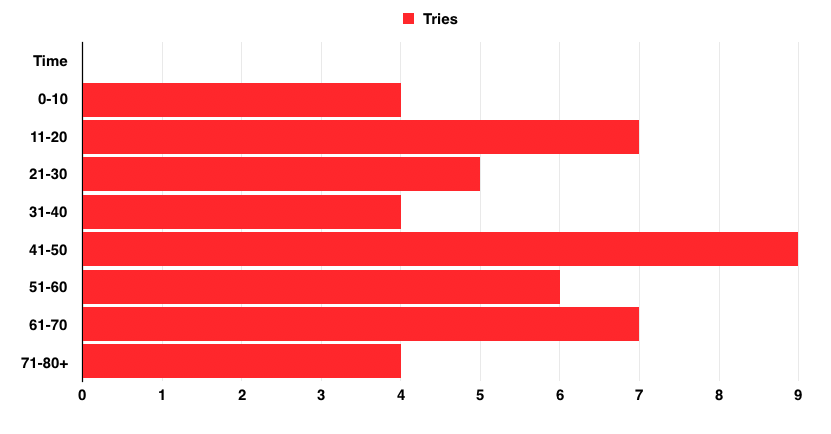

Plucking out random percentages mischievously, Jones also demanded higher fitness levels. With this in mind, the respective timings of England’s tries is an interesting gauge of his progress:

A return of 26 second-half tries to 20 scored in the first stanza is encouraging in that regard. More heartening still is that the highest grouping of nine tries arrives between 41 and 50 minutes.

In any sport, the period directly after half-time is considered pivotal. Saturday’s defeat of Australia reaffirmed this truism. Following a disastrous opening from England and an underwhelming first half, Marland Yarde dotted down on 44 minutes before Youngs added another try five minutes later. The Wallabies were hit with a one-two combination and never recovered.

Personnel and positional breakdown

Without a deliberate knock-on from Argentina wing Matias Orlando, Tom Wood certainly would have collected a scrum-half pass from Chris Robshaw to become the 24th try-scorer of England’s 2016.

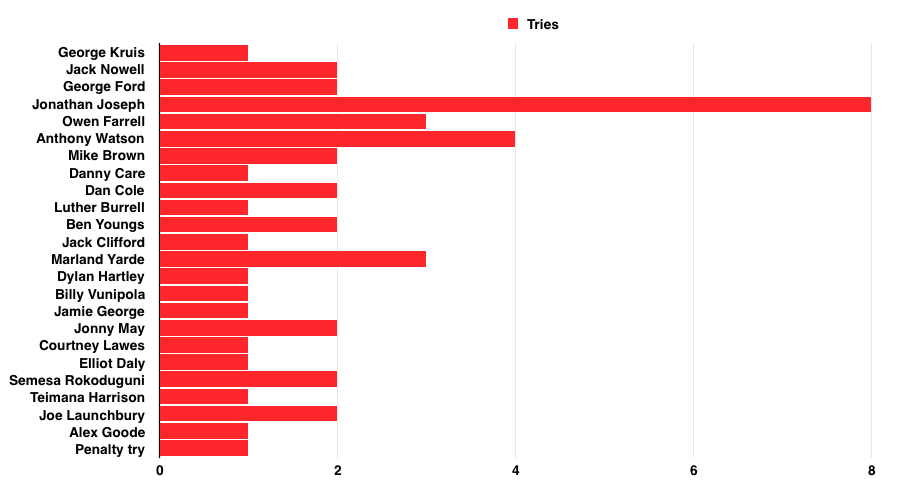

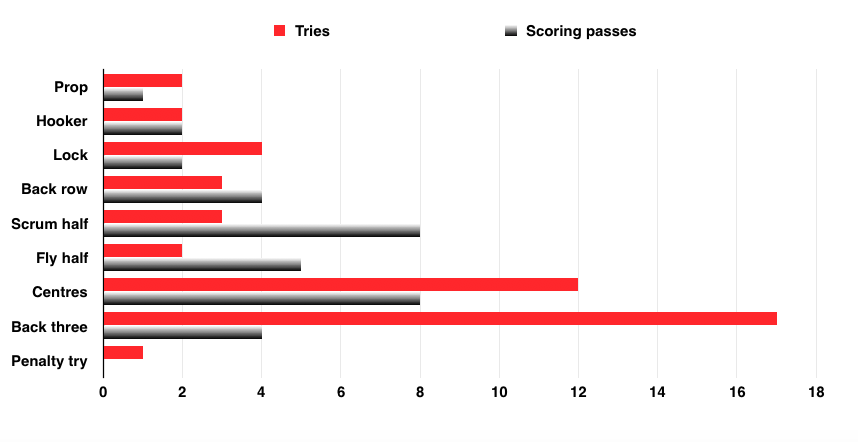

As it was, a penalty try was awarded by referee Pascal Gauzere. This features in the final haul in the a list alongside 14 backs – responsible for 34 tries – and nine forwards sharing 11 more:

If 2015 saw Jonathan Joseph emerge as an attacking influence at international level, coaxing would-be tacklers on to their heels before gliding around them and into space, the Bath centre’s defensive qualities have underpinned the success of the Jones era to date.

Joseph’s spatial awareness and decision-making – his instinctive understanding of when to shoot out of the line and when to drift across-field – have thwarted many attacks. What is more, his opportunism has manufactured five tries (out of a team-topping total of eight) from turnover ball, including three clean interceptions.

The graph below shows the positional profile of England’s scorers, accompanied by a tally of assists:

Above all, these figures are testament to attacking variation. Eight scoring passes from scrum-halves suggests a reliance on narrow, abrasive running. However, 37 per cent (17/46) of England’s tries were finished off by wings or full-backs. Nine assists from tight-five forwards attests to distributions skills across the board, whether transferring the point of contact in tight exchanges or roaming out wide.

This ‘scoring pass’ category counts recovered kicks, an area in which England excelled. Seven different players – Danny Care, Ben Youngs, George Ford, Owen Farrell, Jonathan Joseph, Anthony Watson and, of course, Jamie George – used the boot to create a try.

Another three tries were fashioned by kicks recovered earlier in attacks. Dan Cole’s effort against France was set up by two in succession – Ford’s cross-kick to Watson preceding a chip in-field to Joseph.

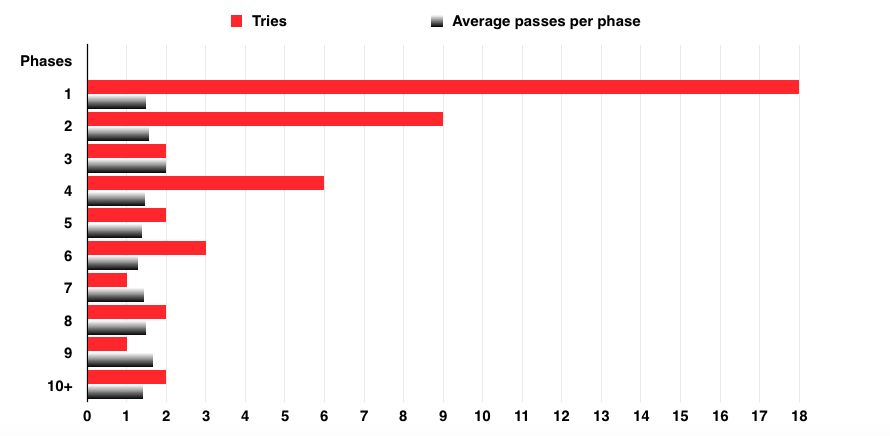

The data from England’s phase-play offers a clearer idea of their flexibility.

Painting patterns

The primary red blocks on this graph separate England’s tries into the number of phases in a scoring attack. The secondary grey blocks detail the average number of passes per phase in those attacks.

For example, a try might be scored from a scrum after four phases following this pattern: Carry from number eight at the base (zero passes) > carry from first-receiver (one pass) > carry from first-receiver (one pass) > try in the corner (three passes). The average passes per phase of that score would be 1.25 – a total of five passes in the move divided by four phases.

Only one grouping reaches an average mark of two passes per phase, emphasising the establishment of Eddie Jones’ preferred ‘ruck and run’ rugby. This approach hinges on rapid ball retention, with a high volume of one-out runners and pick-and-gos.

It is a system that suits England’s powerful, dynamic pack. Crucially, Jones has honed attacking breakdown standards to help inject pace and provide a foundation for this style of phase-play.

First-phase tries make up a shade under 40 per cent of England’s total for the year. The figure is boosted by quick scores from turnovers and from close-range set-pieces. Tries such as these are likely to consist of zero passes – think of an interception or a driving lineout maul.

This representation is useful for an overview of England directness this year, but tries such as Jonny May’s against South Africa – a five-pass, first-phase strike move from a lineout – get buried by other data.

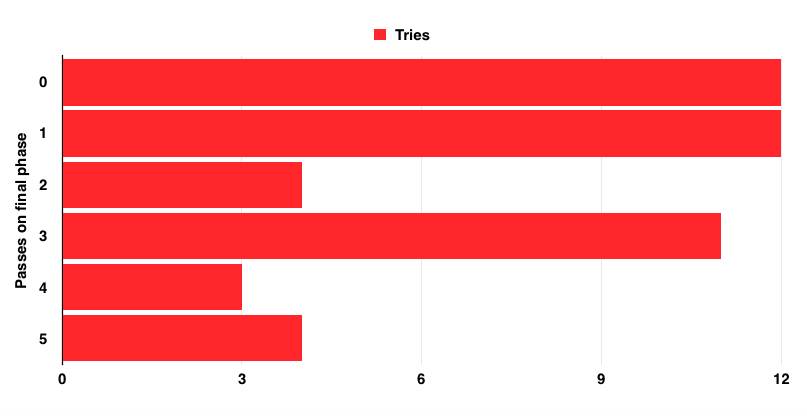

For that reason, here is a final graph detailing the number of passes on each decisive phase:

That a 52 per cent share of tries required one pass or fewer on the final phase emphasises England’s punchy approach, their set-piece prowess and opportunistic scavenging.

That said, 18 tries arrived after three or more passes on the final phase. This explains the high number of assists from fly-halves, centres and back-three players in the earlier positional breakdown of scoring passes. Another hallmark of 2016 has been an ability to move the ball into space under pressure from desperate goal-line defences.

Beyond the brushstrokes

Here are a handful of statistics that you will not be able to gleam from these graphs:

- Owen Farrell contributed to six try-scoring turnovers, two from robust tackles in the dying stages of the Tests in Brisbane and Melbourne

- Five scoring phases were started by a player other than a scrum-half passing the ball from a ruck, highlighting England’s skills as well as their appreciation of and commitment to generating quick ball

- Only three tries – Farrell’s against Italy (Jamie George), Dan Cole’s against Australia in Sydney (Ben Youngs) and Semesa Rokoduguni’s first against Fiji (Alex Goode) – were directly assisted by an offload out of tackle. Reflecting Jones’ ‘ruck and run’ ethos and confidence in their breakdown skills, players generally priortised winning collisions and ball presentation

- Four try-scoring turnovers came from England’s kick-chase, a staple of the ‘fish and chip’ rugby Jones jokes about

Appropriately, with a Six Nations on the horizon that is to trial bonus points, England’s resolution for 2017 will be to increase the volume of their try-scoring.

This superb piece from Murray Kinsella of The42 outlines that the All Blacks can hurt teams from anywhere. Steve Hansen’s charges ended 2016 on 80 tries from 14 matches – close to double the total England managed from one more game. As an inspired Ireland proved in Chicago, scoring five tries to New Zealand’s four, you must out-gun the world leaders in order to beat them.

England will not be sitting back in cushy satisfaction. They must spend next year fine-tuning their weapons.