Fax machines and faith – the inspirational story of how the women’s game beat the odds to forge its own global journey

On the 20th June 1987, the inaugural Men’s Rugby World Cup final was jointly hosted by Australia and New Zealand, writes Nick Heath.

In front of more than 48,000 spectators at Auckland’s Eden Park, Grant Fox kicked 17 points among three tries as the All Blacks defeated France 29-9.

By contrast, nine years earlier, University College London student Deborah Griffin was helping to organise the first women’s rugby match between UCL and rivals King’s College.

It was the start of a journey in the game that would see Griffin deliver the first-ever Women’s Rugby World Cup and go on to become the Rugby Football Union’s first woman president this summer.

“Yeah, we’re going to do this.” By the late 1980s, women’s rugby had existed in various forms for decades, but it remained fragmented and largely unsupported.

Women had been playing the sport in countries like France, New Zealand and England since at least the 1960s, often organising club matches informally.

Read more: All you need to know about the 2025 Women’s World Cup

In 1983, the Women’s Rugby Football Union (WRFU) was formed in England, and in 1985 an unofficial European championship was staged between France, Great Britain and the Netherlands.

Despite growing interest, the sport faced persistent sexism. Rugby was widely perceived as a male domain – too physical, too aggressive, too ‘unfeminine’ for women.

Female players struggled for playing kit, pitch access and transport, and coaching was often self-funded. Media coverage was negligible and governing bodies offered little to no support.

How the Women’s World Cup began

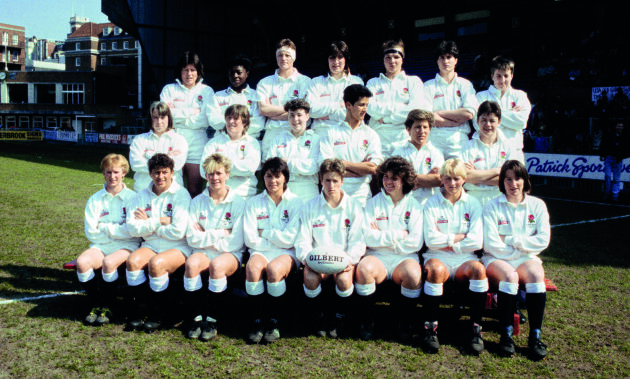

The England team pictured before the final of the inaugural Women’s Rugby World Cup Final between the USA and England. (Photo by Stu Forster/Hulton Archive)

As 1991 dawned, the men’s international game was preparing for its second global tournament. Griffin, then a member of Richmond Women’s rugby club and involved with the WRFU, returned from a club tour in New Zealand with a radical idea.

Why not organise an international tournament for women’s teams?

She recalls: “I never had a grand plan, it was about what’s the next thing to do. I wrote a paper for the Women’s Rugby Football Union, which I was still on, and they said, ‘Great idea, go ahead and do it!’. I’m not sure I expected that answer from (the secretary) Rosie Golby.”

Crucially, Griffin insisted that she would only undertake the project if she could choose her own organising committee, not one imposed upon her. This was a bold but necessary demand.

She wanted to build a team rooted in trust, competence and with a shared vision. She turned to her Richmond team-mates: Sue Dorrington, who brought commercial experience; Alice D Cooper, who had a background in PR and advertising; and Mary Forsyth, an accountant.

As Forsyth later explained, the team’s cohesion and shared sense of purpose allowed them to “hit the ground running”. Cooper adds, “I don’t think at any point we thought it was a bad idea. We thought, ‘Yeah, we’re going to do this’.”

What they lacked in official backing and experience, they made up for in creativity, tenacity and sheer belief. Their dynamic would be essential in overcoming the bureaucratic, logistical and cultural hurdles of the time. As the call went across the UK for potential host cities and venues, it was the Sports Council for Wales who indicated strongest interest.

Related: How the 2014 Women’s World Cup was won with Nolli Waterman

The WRFU was overseeing the game in a manner that included both Wales and Scotland as well as England, so the idea of a committee of club players from England staging the tournament in Cardiff wasn’t as curious as it may sound today.

With the promise that the tournament could use the National Sports Centre in Cardiff’s Sophia Gardens to host the dinner and have access to the gym, swimming pool and squash courts for any training needs – all for free – the case for Wales was strong.

After tapping up Cardiff Arms Park as a venue for the semi-finals and finals, plus support from the WRU to encourage other club venues to host matches, Griffin and her committee settled on the various sites across Wales for the tournament.

From the ground up

Without the internet or mobile phones, communication with international teams required patience. The organising group reached out by fax – a technological relic by today’s standards but critical at the time.

Dorrington recalls the thrill as confirmations started coming in from around the world. “When we started faxing the teams, and they started faxing back to say ‘we’re in’, we knew it would happen.”

Twelve national teams eventually signed on: USA, England, France, New Zealand, Canada, Netherlands, Japan, Italy, Sweden, Spain, USSR and Wales.

Each country bore the cost of participation themselves – no federations were funding these women. The players took unpaid leave, held fundraising events and, in many cases, paid out of their own pocket for the opportunity to represent their nations.

Despite its scope and significance, the IRB (now World Rugby) refused to endorse the tournament, questioning whether a women’s World Cup could generate enough interest or organisational competency. They even threatened the use of a logo that had been drawn up, which was duly modified to avoid copyright.

This left the tournament without official status, funding or access to major infrastructure. Resolute, the fearless four women pressed on.

The Women’s Rugby World Cup founding four

Held in South Wales in April 1991, the first Women’s Rugby World Cup took place across modest venues. Journalists such as Stephen Jones, the Sunday Times’ correspondent and Rugby World columnist, and the Daily Mail’s Peter Jackson gave the tournament what coverage they could.

The BBC’s Rugby Special showed the competition in a brief round-up. Editors’ attitudes of the time clearly decreed that women’s rugby should still only command the smallest of column inches and briefest of airtime.

Tale of the tournament

The tournament was not without a memorable tale or two. At one stage the hotel that the England team were staying in declared that they had accidentally double-booked rooms and that the players would have to vacate.

A compromise was reached which saw the ejected individuals all housed together in one of the conference rooms on temporary mats and makeshift beds. Not ideal prep for an international team.

What of the Russian side? After arriving at Heathrow without any plans for their onward transfer, an unexpected call was received by the organisers that they needed collecting.

A fleet of minibuses was swiftly obtained and players and volunteers helped round them up. Having settled the Russians into their new Welsh environment, it was a call from HM Revenue & Customs that was the next significant moment for the committee.

Their players had been caught selling vodka and caviar that they had brought over with them on the streets of Cardiff, in return for cash to help pay their way. In the end, the strength of the language barrier meant that all involved opted to turn a blind eye.

Read more: How the 2021 Women’s World Cup was won

Victorious USA player Patricia ‘Patty’ Jervey holds aloft the Women’s Rugby Union World Cup Trophy. (Photo by Howard Boylan/Allsport/Getty Images/Hulton Archive)

On the field, the final saw the USA defeat England 19–6, with a powerful display of running rugby and strong forward play.

England, who had shown class and consistency throughout the tournament, were disappointed but knew they had been part of something bigger than the result.

The real victory was the very existence of the tournament itself. The 1991 Women’s World Cup wouldn’t be officially recognised by the IRB until 2009. For nearly two decades, the achievements of the players and organisers went unacknowledged by the sport’s governing body.

The oversight spoke volumes about the entrenched attitudes towards the women’s game and the systemic barriers female athletes continued to face.

Momentum

Yet the tournament had started something. Inspired by the success of 1991, the next Women’s World Cup was planned for 1994 and took place in Scotland, having initially been scheduled for Amsterdam.

England took revenge on their USA rivals in the final, winning 38-23. Victorious players from that squad have gone on to play key roles in the women’s game: Gill Burns MBE has lent her name to the annual English Women’s County Championship; Giselle Mather (née Prangnell) is head coach of Team GB Sevens having coached at Trailfinders and Wasps; Nicky Ponsford is director of high performance at World Rugby; Genevieve Shore is executive chair of Premiership Women’s Rugby.

Women’s rugby has grown exponentially.

The 2014 tournament in France saw record attendances and broadcast audiences. The 2017 edition in Ireland drew over 45 million viewers globally. And in 2021 (delayed to 2022 due to the pandemic), New Zealand hosted a landmark event at Eden Park, drawing unprecedented crowds and media attention.

The World Cup is now central to the women’s rugby calendar, with the tenth iteration this year in England already breaking records, with over 300,000 tickets sold and with a raft of new commercial partnerships that demonstrate the global interest in the game. It’s easy to forget just how fragile the 1991 Women’s World Cup really was.

Without official recognition, financial support and minimal media coverage, it was a miracle of coordination and courage. That it succeeded is a credit to the women who dreamed it into existence.

Deborah Griffin, Sue Dorrington, Alice Cooper and Mary Forsyth were inducted into the World Rugby Hall of Fame in 2022. These four founders didn’t just organise a tournament.

They built a legacy and blazed a trail for generations to follow. Cooper is now directing a documentary of the 1991 story, which is crowdfunding via Greenlit.

Download the digital edition of Rugby World straight to your tablet or subscribe to the print edition to get the magazine delivered to your door.